A big thank you goes to my daughter Caitlin for creating the image above.

Folk music, in its broadest definition, is music that is handed down within a given tradition. This can apply to Tuvan throat-singing, Mexican polkas, or even English murder ballads. Or to the blues. Indeed, many American folk singers include blues songs in their repertoires, and some show the influence of it in everything they do. Still, there is a qualitative difference between a folk artist performing a blues song and the performance of a blues musician. To me, the difference is the approach to the song. A folk artist emphasizes the song in their performance. The lyrics are clear, and the playing likewise. This can be done in an emotional way, and I thoroughly enjoy these kinds of performances. But a blues artist takes a song, any song, and focuses on the emotion of the piece. The performance is raw, with everything out in the open. Subtlety comes from the shades of emotion in a performance, in conveying a glimmer of hope amidst the sorrow, or love amidst the anger.

The above makes it sound like there is a sharp line between a folk performance and a blues one. But life is rarely so neat, and so it is here as well. There are degrees of “folkness” and “bluesness” in the performance styles of most artists who plow the ground where the two meet. Let’s meet some of these artists, and I’ll show you what I mean.

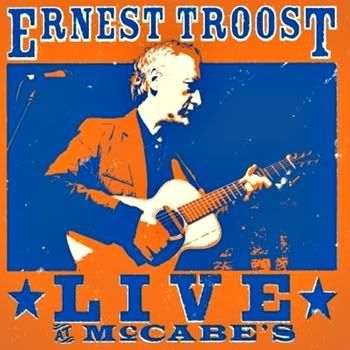

Ernest Troost: Real Music

[purchase]

Ernest Troost was a New Folk winner at Kerrville a while back. He plays acoustic guitar, and his playing style shows that he knows well the styles of the great pre-war blues masters. As a writer, Troost’s work is informed by the blues, but not bound by it. His approach to vocals is folk all the way. His words are important, and he is emotionally invested, but he’s keeping some for himself as well. Live at McCabe’s presents a selection of Troost’s songs from his three studio albums to date. The show begins with just Troost and his guitar, and the band members join him one by one. So some of the songs are presented in sparer arrangements than the studio versions, while others have a fuller arrangement than before. Over all, Live at McCabe’s is a great introduction to the bluesy folk of Ernest Troost. He is new to me, but I will be keeping an eye on him from now on.

Grant Dermody: First Light

[purchase]

Thank you, Marco Prozzo, for the cover image. You can see more of Prozzo‘s work here.

Two of the best know acts working this ground between folk and blues would be Eric Bibb, from the folk side, and the duo of John Cephus and Phil Wiggins, from the blues side. Grant Dermody has worked extensively with both. His album Lay Down My Burden has liner notes by Phil Wiggins, and Eric Bibb plays on several songs. Dermody is a singer and Harmonica player, and he has the Piedmont blues style down. Dermody also knows how to write in this style. And his choices of covers include many of the old masters. But Lay Down My Burden closes with a Tibetan chant, and the album also includes a wonderful version of Amazing Grace. Dermody is also a creative arranger. A couple of songs here feature just two harmonicas and voice, and other songs have a four piece band, but with mandolin where you would expect a guitar. So First Light is solidly in the blues tradition, and a Dermody original, but elsewhere, Dermody explores the boundaries of the blues, and sometimes steps outside of them. Over all, he shows himself to be a confident musical explorer. He is also a generous band leader, sometimes stepping back and giving the lead vocals to someone else. If you buy only one album from this post, it should probably be this one, because Dermody most eloquently sums up the theme of this post in his album, and it is a thrilling trip.

Mary Flower: I‘m Dreaming of Your Demise

[purchase]

Mary Flower is here for a couple of reasons. She likes to open her songs with just her guitar, before adding her voice and a second instrument, and those guitar intros are pure blues playing. Also, I’m Dreaming of Your Demise add the piano of Dave Frishberg, so the song makes a good bridge to the piano blues in the rest of this post. But Mary Flower’s singing is a wildcard here. This is neither a folk nor a blues approach to the song. Instead, Flower is a jazz singer. Dreaming is a song sung by a wronged lover seeking revenge, but it is even more chilling because it is delivered with a wink and a smile. The structure of the song, with its extended lines in the vocal part, also place it in the jazz tradition But Flower’s playing is blues all the way. The best measure of her enormous talent is that she makes this combination sound completely natural, even though I’ve never heard anyone do it before.

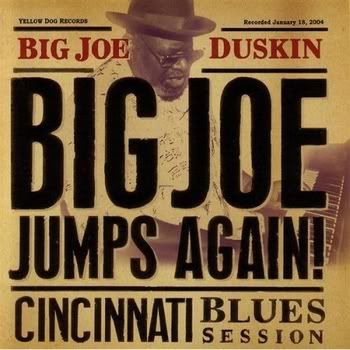

Big Joe Duskin: Get Out of My Way

[purchase]

Big Joe Duskin was a throw-back. Born in 1921, Duskin began performing before World War II, playing piano in the classic boogie woogie style, and singing in a manner that is pure blues. However, Duskin did not make his first album until 1978. By then, he was living representative from another world, that of pre-war blues. Duskin died in 2007, and Big Joe Jumps Again! Was made three years before that. In all, Duskin only made three studio albums and two hard-to-find live ones. Boogie woogie is usually thought of as fast music, but I chose Get Out of My Way to show how Duskin could burn up a slow number as well. I love the ornamentation, played mostly in the right hand, that changes from verse to verse. Duskin’s voice had to have been stronger when he was younger, but all of the emotion this song needs is there. I can imagine the then 83-year-old Duskin shouting to the drummer and bass player on these sessions, “Try to keep up!”.

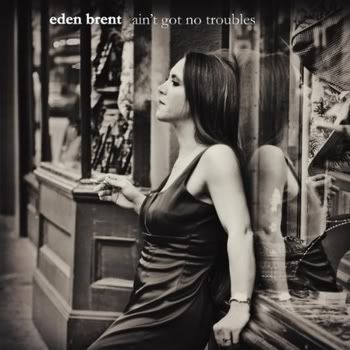

Eden Brent: Ain‘t Got No Troubles

[purchase]

If you haven’t listened to Ain’t Got No Troubles yet, hold off for just a second. Forget that this is a blues post, and look at the picture of the woman on the album cover shown above. Try to imagine what her voice must sound like. Got it? OK, now listen. Wow! Where did that come from? Eden Brent is an old fashioned blues belter, and a fine one. She is also a New Orleans blues pianist in the tradition of Professor Longhair and Dr John. That said, she has a wonderful light touch on her solos, dancing across the keys while never losing the backbeat. She is surrounded by a great band, including George Porter Jr of The Meters. Some people may think of the blues as depressing music, but this album is a fine example of how exciting this music can be, and why such a wide variety of artists are drawn to it.