My first encounter with folk music came when I was a child in the 1960s. Folk came in two flavors in those days. There were solo performers like Pete Seeger and Joan Baez, who sang traditional songs and accompanied themselves with just a guitar or banjo. And there were groups like Peter, Paul, and Mary, usually trios, who might sprinkle in the occasional original or contemporary number, but were still folk because at least most of their material was traditional. The music was strictly acoustic. The subjects of the songs were the usual love and mayhem of traditional songs, plus a mix of protest songs.

Of course, things have changed, starting with Bob Dylan’s notorious performance at the Newport Folk Festival. Dylan plugged in, and performed original songs. The first result was that Dylan was denounced as, (horrors), not folk. But nowadays, most folk artists use some electric instruments, and original and modern songs are more often heard than traditional ones. For this set, I present five artists and bands who start almost from the foundation I first heard so long ago. But these artists write their own songs, and so they express a wider set of experiences than the music of my youth. They don’t rule out arrangements that may use plugged in instruments, but their sound is mostly acoustic.

The Weather Station: Everything I Saw

[purchase, price in Canadian dollars]

The Weather Station is Tamara Lindeman. There are three other musicians helping her out, but she is calling the shots. Lindeman plays guitar and banjo, and the arrangements here focus on her. Everything I Saw opens with Lindeman singing in a breathy near-whisper about the plants she grew in her garden, and you think this will be a neo-hippie flower-power song. But very soon, Lindeman shifts gears. The song becomes requiem for a relationship that has died. The narrator tells us of how she gave everything to this man she was involved with, and finally realized that she was getting nothing back. The intensity in Lindeman’s voice increases as the song goes on. The result is a powerful emotional statement, one of many on this album.

Jon Brooks: Cage Fighter

[purchase]

Jon Brooks is a storyteller. His songs present characters you don’t usually meet on old folk albums. Some of his characters lead lives filled with violence, but they still find their own personal form of grace. This is nowhere more true than in the song Cage Fighter. The protagonist here grew up as a child soldier in Sarajevo. From that, he became a Cage Fighter, like Wolverine was in the first X-Men movie. The fighting was real, and so were the injuries, but the narrator of the song describes the feeling of being in the cage as “Zen-like”. As listeners, we may be appalled but what this character did, but we sympathize with him as well. It takes a great writer to pull this off, and Brooks is.

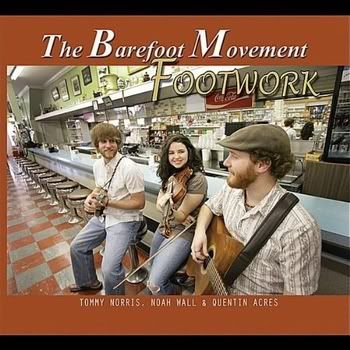

The Barefoot Movement: Tobacco Road

[purchase]

The Barefoot Movement is a trio, with guitar, mandolin, and fiddle. On this album, there is also an upright bass to fill out the sound, and, only on Tobacco Road, a cello. The fiddler, lead singer, and main songwriter, is Noah Wall. I am fairly sure that it is physically impossible to play the violin and sing at the same time, so Wall plays fills and brief solos between verses. This Noah is a woman, and she sings in a wonderfully emotive folk soprano. Lyrically, Tobacco Road would seem to be the closest to traditional themes of any song in this set, but a close listen reveals layers of meaning. The song opens with the images, beautifully drawn in just a few short lines, of a farm that has fallen on hard times. On the surface then, the song is a story of a farm that has known better times. But Tobacco Road can also be taken as a portrait of a relationship that has changed as the rush of youthful first love has given way to age and the changes that come over time. In the end, this is a song about perseverance in the face of adversity, with the personal reflected in the condition of the soil and crops. It’s a great piece of writing, and Wall and Co back it up with a wonderful performance.

ellen cherry: 1998: The Things I Long For and the Things I Have Are Not the Same

[purchase]

Each song on (New) Years imagines a woman in a different year, from 1864 to 2010. The first six songs on the album fall in 20 to 30 year intervals, or roughly one for each generation. The last six songs are more closely clustered, with songs for 1983, 1998, 2002, 2003, 2005, and finally, 2010. The years chosen are not always the obvious ones, with no songs for the years of either World War, and no song for the 1960s or 2001. ellen cherry plays mostly guitar and some piano, and her style can be folk, jazz, or something in between, as the song demands. She also sings equally well in either style, a rare gift. This allows her to change the style of the music as she moves through the years, and she does this masterfully. Stylistically, 1998: The Things I Long for and the Things I Have Are Not the Same falls between jazz and folk. In the song, cherry takes us back to one of the last years in which you could easily find a pay phone, and imagines the woman’s part of a conversation with her lover. The strength of the writing and the emotion of the performance allow the listener to fill in the other side of the conversation. This is the magic of cherry’s writing. She provides a portrait of her character in such a way that we get to know the people in their lives, even though we never meet them.

Sinful Savage Tigers: The End of the Horse Drawn Zeppelin

[purchase]

Sinful Savage Tigers are also a trio. Between them, they play guitar, harmonica, banjo, mandolin, and every song has a stand up bass. Guest musicians provide fiddles, percussion, and dobro. All of this adds up to a sound that I would call modern stringband. All of the songs have a swing to them. The End of the Horse Drawn Zeppelin is a song that takes the phasing out of an old technology as a metaphor for the end of a relationship. There is a recognition of the need to move on, but also a powerful sense that something of value has been lost. The song is a fine example of the band’s ability to powerfully evoke emotion through indirection, with a strong performance to back it up.

2 comments:

Tim O'Brien can sing and play fiddle at the same time.

It's definitely possible to sing and fiddle at the same time. Not easy, really. But this is often why you see old-time fiddlers holding the fiddle against their chest, rather than under their chins.

Post a Comment